“This is the message that ye heard from the beginning, that we should love one another. Not as Cain, who was of that wicked one, and slew his brother…For all the law is fulfilled in one word, even in this; Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.” (I John 3:11-12, Galatians 5:14)

“Among the Hottentots it was the custom for one who had more than others to share his surplus till all were equal. White travelers in Africa before the advent of civilization noted that a present of food or other valuables to a “black man” was at once distributed; so that when a suit of clothes was given to one of them the donor soon found the recipient wearing the hat, a friend the trousers, another friend the coat.

The Eskimo hunter had no personal right to his catch; it had to be divided among the inhabitants of the village, and tools and provisions were the common property of all.

When Turner told a Samoan about the poor in London the “savage” asked in astonishment: “How is it? No food? No friends? No house to live in? Where did he grow? Are there no houses belonging to his friends? The hungry Indian had but to ask to receive; no matter how small the supply was, food was given him if he needed it; “no one can want food while there is some anywhere in the town.”

The North American Indians were described by Captain Carver as “strangers to all distinctions of property, except in the articles of domestic use…They are extremely liberal to each other, and supply the deficiencies of their friends with any superfluity of their own.” “What is extremely surprising,” reports a missionary “is to see them treat one another with a gentleness and consideration which one does not find among common people in the most civilized nations.

In 1587, a group of English settlers established a colony on Roanoke Island, now part of North Carolina. Eleanor White Dare, daughter of Governor John White, gave birth to Virginia Dare—the first English child born in the Americas. Governor White returned to England for supplies but on his return found the colony abandoned, with only the word “CROATOAN” carved into a wooden post as a clue to their fate.

Native American author Maynor Lowery of the 2018 book “Lumbee Indians: An American Struggle,” argued that “The Indians of Roanoke, Croatoan, Secotan and other villages had no reason to make enemies of the colonists. Instead, they probably made them kin.”. The whole premise that assumed the colony was lost implied that Native people had disappeared too, “which we didn’t.”

The men arrived expecting a new Eden with fruit falling from the trees and friendly natives by their side. They soon found they had to tame the forest to grow food and that they were actually invaders facing hostile natives. Within the first year at Jamestown most recruits had died from disease and starvation. During sixteen years of bringing in fresh recruits, eighty percent of some six thousand would-be colonists died from what historians deem depression-induced suicide, whether or not there was an overt act to destroy a life. Isolated immigrants are especially vulnerable to a loss of hope. In 1880, suicides on the Western frontier ran a hundred times higher than they do across America today.

And there were also overt acts of murder.

Without settled agriculture – think Cain’s predicament – within nine months all but 38 settlers are dead, replaced by more settlers on supply ships from England.

The last supply ships of 1608 were lost in a hurricane, and the settlers resorted to stealing food from the neighboring Powhatan tribe. In the absence of reciprocity, they of course defended their means of survival by besieging the fort, now containing 300 settlers. The besieged ate the horses, dogs, cats, mice until they were gone. George Percy wrote: “nothing was spared to maintain life and to do those things which seem incredible, as to dig up dead corpse out of graves and to eat them, and some have licked up the blood which hath fallen from their weak fellows.”

Endocannibalism is where a group eats its own members. This type of cannibalism can be practiced if a group is starving and very young or very old members might be eaten in order that the effective (i.e., working and reproductive) members of the group may survive.

Archeologists found the dismembered bones of a 14 year old girl from a trash pit at Jamestown with cut marks on the facial bones showing clear signs of cannibalism, and two different types of cut scars on the skull and leg bones indicative of two different butchers – one more experienced than the other.

By Spring only 60 out of the 300 people trapped in James Cittie survived to greet the next resupply ship. The remaining 240 skeletons have not been found, which is far more indicative of mass murderers hiding their kills than Christians respecting the dead in a quasi-“this is my body, take, eat”.

Archeology validates the biblical timeline of a oppression-based civilization beginning east of Eden shortly after Creation ~4,000 BC.

From Louis Ginzberg’s collection of Jewish legends (published 1909)

He first of all set boundaries about lands: he built a city, and fortified it with walls, and he compelled his family [tribe, not necessarily kin] to come together to it; and called that city Enoch, after the name of his eldest son Enoch.

The mix of people brought together in Cain’s city provided the first opportunity for diversification of labor, freeing some people from the daily grind of food production to engage in cerebral pursuits, inventing technologies and creating the arts. “in the city are gathered, rightly or wrongly, the wealth and brains produced in the countryside; in the city invention and industry multiply comforts, luxuries and leisure.”

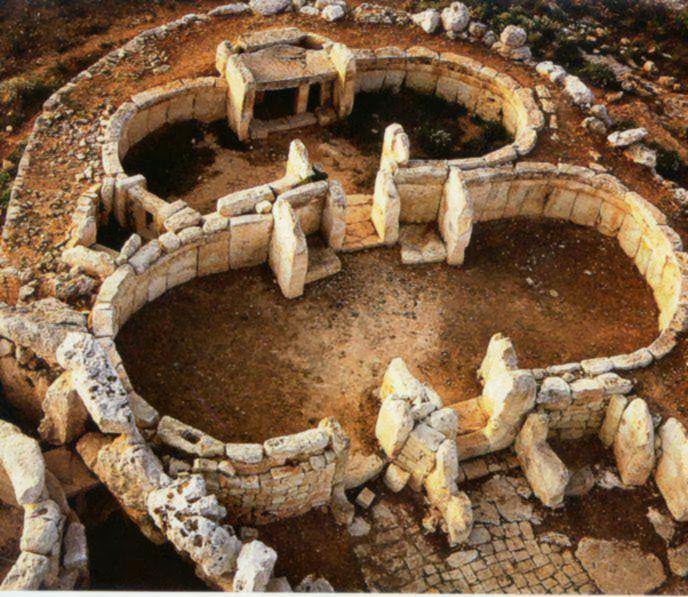

Catalhoyuk housed 3,000 – 8,000 people in 32 acres. It had no streets, instead, houses were packed together wall to wall, no windows or doors, the only access was through a trapdoor in the roof.

A typical Catalhoyuk module contained a single 20-by-20-foot room which was occupied by five to ten members. This allocates a maximum of 8×10 feet floor space per person for minimum occupancy of five members – the size of a walk in closet – with a minimum of 7×6 feet floor space – the size of a king size bed – per person for maximum occupancy of ten members.

This is what the International Committee of the Red Cross recommends as the minimum space allocations for prisoners where bunk beds are used, and without kitchen, bathroom, sick care activities being performed, or children being birthed and reared.

The living spaces at Catalhoyuk were found to be embedded in extensive middens of fecal material and rotting organic material in which archeologists can still identify details such as corpses buried inside the houses while the premises were still inhabited by the occupants.

One dwelling at Catalhoyuk was found to have 64 skeletons buried underneath the floors which were made out of soft mud brought from the surrounding marshes. When a house reached the end of its practical life, people demolished the upper walls…which then became the foundation of a new house.

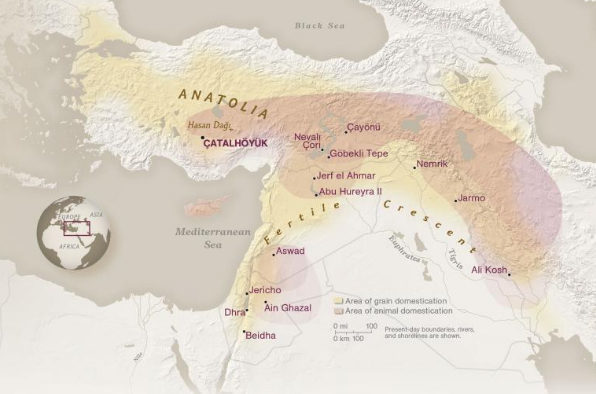

The map below shows that Catalhoyuk is within walking distance to Göbeklitepe, one of the most important archaeological discoveries of our time, revealing ancient wisdom to modern man.

-

Yeah – how the few at the top exploit the masses at the bottom.

“Woe to…the oppressing city!…Her princes within her are roaring lions…Therefore wait ye upon me, saith the LORD, until the day that I rise up…to pour upon them mine indignation.” (Zephaniah 3)

Catalhoyuk was occupied for about 1,700 years. From a biblical perspective, this dates the site from the beginning of the way of Cain until the Flood wiped out the wicked.

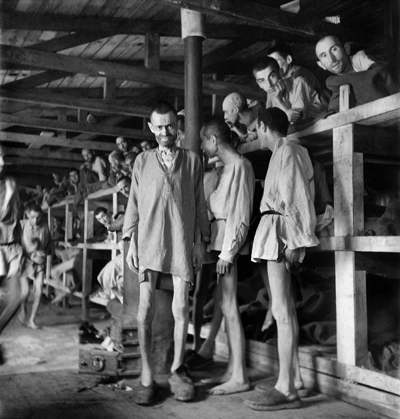

When we take off the glamor glasses of starry-eyed archeologists the picture that emerges is that of a concentration [of persons in a] camp for forced labor, exactly as the Nazis implemented as the productivity basis of its war machine.

[In a boxcar] which was designed to transport ‘eighteen horses’ according to the sign on the door, we were a hundred of us – adults, children, sick, elderly…

The overcrowding in the cars was unbearable, the feeling of suffocation overwhelming, and a desperate struggle ensued for proximity to the narrow window. Growing hunger and thirst magnified the anguish. The necessity to relieve themselves inside the railcar was a nadir for the humiliated deportees. The journey in the freight cars was…often three to four days…occasionally seven to eight days…while some deportees were shuttled around for more than two weeks on boats and trains…

When we finally arrived at “our destination” and the train stopped… the doors suddenly opened…and the Germans started beating us indiscriminately, shouting…Stunned to the point of insanity, people were thrown out [of the car]. I held my child in my arms the entire time. The boy was faint, half dead. At some point…by rampaging Germans…the child slipped out of my arms and disappeared. A mighty wave of people propelled me, trampling everything underfoot. The wave washed over me, too. I didn’t see my child or my family again. In one instant, everything was swallowed up; my whole world vanished as if it had never existed.

The death camp conditions of Catalhoyuk continue to be prevalent in the 21st century, most conspicuously in the Third World countries where desperation forces people to accept starvation wages and disease-ridden living conditions, but even in First World cities where workers are routinely used up and discarded on our own middens of homelessness.

Nearly 13% of the homeless adult population are veterans. Already stressed by an increasing need for assistance by aging post-Vietnam-era veterans and strained budgets, homeless service providers are deeply concerned about the influx of combat veterans from the Gulf Wars. Despite having hazarded their lives, veterans are at a greater risk of homelessness due to lingering effects of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as well as consequent substance abuse.